Light has always been a symbol for God, an image that was used to express the unspeakable mystery and to answer the question about the reason for and purpose of our existence.

„God is light“ says the evangelist John, and wherever God reveals Himself throughout history, an exceptionally bright light appears.

Light does not only brighten the darkness and enable true vision, it also gives and sustains life, it provides us with warmth and a home. Thus, light is the very symbol of God-recognition, the epitome of life and love.

ENCOUNTERING THE LIGHT

The life of Hildegard of Bingen (1098-1179) was also marked by light in all shades and colours until the time of her death, when, according to legend, a radiant light is said to have appeared in the heavens. But even more so, light was the starting point, the igniting spark, and the life-giving fire of her entire work. The encounter with the light struck like lightning in her hitherto completely inconspicuous life.

The life of Hildegard of Bingen (1098-1179) was also marked by light in all shades and colours until the time of her death, when, according to legend, a radiant light is said to have appeared in the heavens. But even more so, light was the starting point, the igniting spark, and the life-giving fire of her entire work. The encounter with the light struck like lightning in her hitherto completely inconspicuous life.

She herself describes it in this way: „In the year 1141 of the incarnation of Jesus Christ, when I was 42 years and 7 months old, a fiery light accompanied by lightning came down from heaven. It flowed through my brain and glowed in my chest. And suddenly the meaning of Scripture was disclosed to me…“ And she heard the instructions: „Write down what you see and hear!“ The penetration of the light and the gift of vision connected with it gave Hildegard of Bingen the reputation of a seer and prophetess. Who was this woman who held her contemporaries spellbound as much as people in our day who are searching for meaning, wholeness and healing?

Is it worth getting to know her life and work and to become absorbed in it? Can we succeed in leaping across the space of 900 years without plunging into the abyss of history? Is there ground for further comparisons between the turn of the first millennium and the one into the third now, other than the general loss of faith and direction and a weakness of character as well as the increasing loss of the Church’s authority? We have very few historically reliable facts on Hildegard of Bingen. She was born in the year 1098 into the House of Bermersheim, a family belonging to the Frankish higher nobility.

According to her contemporary Vita, Hildegard had 9 brothers and sisters and at the age of 14 – as was quite customary then – was given to the recluse Jutta of Sponheim, who lived in a hermitage adjacent to the monastery of Disibodenberg, in order to receive an education. Therefore, from an early age, the Benedictine rhythm of life, alternating prayer and work, study and spiritual reading, community life and solitude, left a decisive mark on Hildegard. In the year 1136 Jutta died and Hildegard took over the spiritual leadership of the small community, which had formed over the years in the hermitage. Up to her 41st year Hildegard’s life moved along the lines of the simple regularity of everyday cloistered life.

Nonetheless, we can assume with certainty, that she acquired a profound education in those early decades of her life. Even though she refers to herself in her later work as an unlearned woman – most likely referring to the fact, that she had not received a formal education in the classical disciplines of dialectics, rhetoric and grammar – Hildegard had a broad knowledge of the bible, theology, philosophy and natural history. Above all, the richness of the Scriptures, which was disclosed to her in the liturgy, in the Rule of St Benedict, and also the study of the writings of the Church Fathers and the Desert Fathers, were to her an inexhaustible source of inspiration, which formed the basis of her entire work. In her writing, knowledge and wisdom, a natural ability for insight and inspired learning blend in inseparable unity.

HEAVEN AND EARTH AS A MIRROR OF DIVINE LOVE

Hildegard’s work had strong visionary and prophetical characteristics, which were totally in line with how she saw herself. For her, divine origin of what she saw and heard in the overly bright light and the awareness of a sense of mission as a prophet belong inseparably together.

Hildegard’s work had strong visionary and prophetical characteristics, which were totally in line with how she saw herself. For her, divine origin of what she saw and heard in the overly bright light and the awareness of a sense of mission as a prophet belong inseparably together.

Her prophetic mind wanted to rouse the people of her time, persuade them to change their ways and act against a growing godlessness. Hildegard perceived herself as God’s advocate, spokeswoman and instrument. Time and again she directed attention to the mystery of the Almighty and disclosed divine love to her readers and listeners as the source and completion of all being. She did not, however, preach a spiritual mysticism or unworldly inwardness.

Her motivation was a religious interpretation of the whole universe and living a consistently Christian life in the world. Everything, heaven and earth, faith and natural science, human life in all its facets and possibilities, was for her a mirror of divine love, and therefore pointed transparently to the Creator. Hildegard of Bingen wrote three large theological works – not because she enjoyed writing, as she repeatedly emphasized, but out of an obligation to make known, what was disclosed to her in her visions. In the preface of her first and main book „Scivias“ (Know the Ways), she describes how great an effort it was to write and how strong the inner resistance was which she had to overcome: „Only when God’s scourge confined me to the sick-bed,…I finally got down to writing…“ What emerged during the next decades of laborious work, was one of the most impressive panoramas of the medieval world – incidentally not seldomly described as the anticipation and basis of Dante’s „Divina Commedia“. In her first work „Scivias“, Hildegard succeeds in spanning the history of salvation from the creation of the world and of man to redemption and fulfilment at the end of time. The never-ending story of God and man, the drama of man’s turning away and back again to his creator is portrayed here in a unique way.

Hildegard attempts to describe the unspeakable mystery of God in ever-new images. Her visions, which are all composed in the same way (1: the vision itself as seen; 2: the explanation of the vision; 3: the theological and spiritual explanation) fascinate the reader in the commanding way in which Hildegard deals with the sources, which she lets flow creatively and freely into her total vision. Equally impressive is the elemental power of imagery in her language, though it must be said that this, at times, does not make it easy for a reader of our own day to comprehend Hildegard’s thoughts and interpretations. In accordance with the wealth of content and versatility of her work, Hildegard also had immense possibilities of linguistic variation at her disposal: she was as much a master of the narrative style as of the dramatic, the scientific as much as the lyrical. She filled old concepts with new meaning, created completely new words, composed songs and hymns and, last but not least, worked as a dramaturge.

THE ONGOING BATTLE BETWEEN GOOD AND EVIL

Hildegard composed and wrote the text to her lyrical drama „Ordo virtutum“ (The Play of Forces) in which she shows the ongoing battle between good and evil, happening over and over again with man and in the world, with 35 dramatic dialogues between virtues and vices.

Hildegard composed and wrote the text to her lyrical drama „Ordo virtutum“ (The Play of Forces) in which she shows the ongoing battle between good and evil, happening over and over again with man and in the world, with 35 dramatic dialogues between virtues and vices.

This allegorical musical drama – the first with musical accompaniment that has come down to us – had its first performance in 1152 at the Abbey of Rupertsberg, where Hildegard, together with 20 nuns, had moved to from Disibodenberg in the year 1150, after a long and difficult dispute. 800 years later, in 1982, a second world premiere followed in the monumental Romanesque ambience of St Martin Major in Cologne.

The basic theme of „Ordo virtutum“ is found in theological terms in Hildegard’s second main work, the „Liber vitae meritorum“ (The Book of Life’s Merits). Here, too, the theme is again and again man having to decide between good and evil, between belief and unbelief, between turning to and away from God: Virtues and vices encounter one another in rhetorically masterful staged disputations and argumentation. These are often interrupted by the words of „vir“ (God), whose form reaches from heaven to the depth of the abyss.

It is Hildegard’s main concern that man is created free, and the decision is placed in his hands for his entire life, to fulfill what is laid down in his creation: to be God’s image. „Man, become what you are: be human!“ This idea could imperceptibly have been taken from Hildegard’s thought.

THE WORLD AS GOD’S WORK OF ART

With her third main work, the „Liber divinorum operum“ (World and Man), which she completes in 1174 after 11 years of work, Hildegard scores another big hit. This colossal work of the cosmos lets the world shine in the eye of the reader as God’s work of art. Out of the elemental force of God’s love flows the creation, the incarnation in the form of the Son and the final redemption of man, who has lost his way, at the end of time in an all-embracing unity.

With her third main work, the „Liber divinorum operum“ (World and Man), which she completes in 1174 after 11 years of work, Hildegard scores another big hit. This colossal work of the cosmos lets the world shine in the eye of the reader as God’s work of art. Out of the elemental force of God’s love flows the creation, the incarnation in the form of the Son and the final redemption of man, who has lost his way, at the end of time in an all-embracing unity.

Man appears as a microcosm, who reflects in his physical and spiritual condition the laws of the whole cosmos (macrocosm). In man, God has portrayed the other creatures and in the human form ordered the building of the firmament and of all of creation accordingly.

„Just as an artist has his moulds with which he makes his vessels“, writes Hildegard, „so God forms man after the structure of the world’s fabric, after the whole cosmos.“

For Hildegard, the basic forms of being are the circle and the cross – symbols of divine love, union and redemption as well as signs of time and eternity. Hildegard’s visions of the cosmos were given a totally unique expression in colourful miniatures, which make them clearly visible in images. 42 miniatures in all are recorded (35 in „Scivias“ and 7 in the „Liber divinorum operum“). All of them were probably not created under her direct influence, but only shortly after her death. Particularly incomparable are depictions of man in the wheel of the cosmos, as is divine love in the form of a woman and the representation of the vision of the Trinity.

Especially striking is the extensive symbolism of colour, taken from medieval iconography, which Hildegard and the painters of miniatures amongst her followers use. Time after time it directs the understanding and interpretation anew to the main basic concern of Hildegard’s work, which she summarizes at the end of her third work in this way: „And again I saw the living light and I heard a voice from heaven, which taught me these words: Now praise be to God in His work, man. For the sake of his salvation He fought the mightiest battles on earth…“

THE UNITY OF SALVATION AND HEALING

Hildegard also visualized the human need for redemption totally within the concept of the inseparable unity of cosmology, anthropology and theology.

Hildegard also visualized the human need for redemption totally within the concept of the inseparable unity of cosmology, anthropology and theology.

According to Hildegard, the light of divine grace lets man recognize his incompleteness and need for healing. Whoever closes himself to this call and abuses his freedom under the illusion of absolute autonomy enters into guilt and sin, falls ill in soul and body and in the end throws the elements of the cosmos into turmoil.

Salvation and healing can therefore only come from turning to God, from faith that brings good works and a moderate way of life, which brings healing and health in a holistic sense. Hildegard’s concern about man’s salvation is also reflected in an abundance of comments on and ideas for natural healing and therapeutical methods. However, to this day the question whether the works „Physica“ and „Causae et curae“ attributed to her, which deal on the one hand with the description of certain medicines and remedies and on the other hand with the treatment of illness, are really hers in their entirety.

To this day we are mostly left in the dark about the sources and history of written records of these works. However, without any doubt, Hildegard’s lasting contribution is her holistic and complete view of man and the world as God’s creative work, as the „Opus Dei“, which on the one hand is a pure gift of the grace of God, on the other makes man a co-creator and gives him the clear and demanding task to work on structuring the world in a humane way.

Chronolgy

1098

Hildegard born in Bermersheim near Alzey

ca. 1112

Enters the hermitage of Jutta of Sponheim, a recluse living near

the monastery of Disibodenberg

1136

Elected abbess of the convent, which had developed from

the hermitage

1141-1151

Work on „Scivias“, numerous compositions and the lyrical

drama „Ordo virtutum“

1147/48

At a reform synod in Trier, Pope Eugene III sanctions

Hildegard’s writings

1150

Moves to the newly built Abbey of Rupertsberg near Bingen

with twenty nuns

1158-1170

Public sermons in Mainz, Würzburg, Bamberg Trier, Metz,

Cologne, and other towns

1158-1173

Work on „Liber vitae meritorum“, on papers concerning healing

and curing illness and on „Liber divinorum operum“

1165

Founding of second convent at Eibingen above the town of

Rüdesheim

1174/75

The monk Gottfried starts work on Hildegard’s Vita

1178

Conflict with the administrators of the diocese of Mainz, who

impose the interdict on the convent of Rupertsberg

17.09.1179

Hildegard dies at Rupertsberg

ca.1180-1190

The monk Theoderich finishes the Vita which Gottfried started

ca.1223-1237

Process of canonization fails for unknown reasons

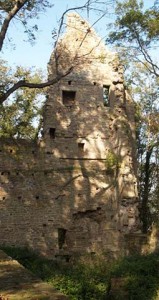

1632

The monastery of Rupertsberg is destroyed during the

Thirty Year War

1802

Dissolution of the nunnery at Eibingen in the course of the

secularization

17.09.1904

Benedictine nuns of the Abbey of St Gabriel in Prague settle

in the newly built Abbey of St Hildegard above the former

monastic site at Eibingen

1978-1994

Critical editions of all of Hildegard’s main works published

1997/1998

Jubilee Year commemorating the 900th birthday of St Hildegard

THE MOMENTUM OF THE UNVARNISHED TRUTH

Hildegard also expressed her prophetic concerns most distinctively in her letters. From her extensive correspondence, 390 letters have come down to us: testimony of her intrepid directness, admonishing concern, refreshingly humorous generosity, personal commitment and far-reaching exertion of influence in (church) politics.

Hildegard also expressed her prophetic concerns most distinctively in her letters. From her extensive correspondence, 390 letters have come down to us: testimony of her intrepid directness, admonishing concern, refreshingly humorous generosity, personal commitment and far-reaching exertion of influence in (church) politics.

She once wrote to a disheartened, self-tormenting abbot: „Remember that you are an earthly man and do not be so afraid, for God is not looking for too much of the heavenly in you!“

One can gather from all of her correspondence that Hildegard was a well-recognized authority in her lifetime. Her advice was sought after, even when it was unpleasant and on no account complimentary. Her contemporary biographers report the same of her sermons, which she preached in market squares and cathedral precincts all over the country: in Cologne, Trier, Metz, Würzburg and Bamberg, in Siegburg, Eberbach, Hirsau, Zwiefalten and Maulbronn. If travel for a nun of the 12th century wasn’t outrageous in itself, the content of what she expected her audience to listen to was often enough a scandal for them. Yet Hildegard was everything but a revolutionary.

Her theology was quite orthodox, her visions strictly ecclesiologically orientated, and her image of man corresponded completely with the biblical basis. What was it then that fascinated people with this woman and to this day makes the name of Hildegard of Bingen appear to be so unmistakably distinct and relevant?

Was it her radical honesty, her uncompromising defense of the truth, which she saw in the heavenly light and which at the close of the first millennium, no one supposedly wanted to hear about anymore? Was it her powerful language rich with imagery that knew how to bring „old“ truths close to people in quite a new way? Was it her truly cosmic theology that made the inseparable unity and meaningfulness of all life appear in a totally new light? Hildegard was and is a person who can stir us, a thorn in the flesh of the church and the world.

She was a prophet in the true sense: unafraid, clear, and consumed by the fire of radical discipleship. To the very end she remained a champion of a faith, that was to be fully lived, and an advocate for love and justice. An event shortly before her death shows this again: Hildegard had the body of a young nobleman buried in the cemetery of her convent, who had previously been excommunicated, but by receiving the sacraments before his death had returned to the church.

The bishop of Mainz’s prelates, who did not know about the young man’s change of ways, demanded the body to be exhumed, since he should not have been buried in consecrated ground. Hildegard refused and prevented the enforced handing over by having the cemetery ploughed over, so that the grave of the young man could not be identified. Hildegard’s unwavering attitude was punished with the interdict. The monastic community was deprived of its core: Hildegard was barred from public worship and from receiving communion.

Only after two years of a dogged struggle, the Abbess of Rupertsberg finally achieved the reversal of the interdict. But her remaining vitality had now been exhausted. Hildegard died on September 17th, 1179. A few years after her death, in 1223, the process of canonization was initiated. Why this came to nothing has never been clarified. In a more recent effort the German bishops tried in 1978 to have the title of Doctor of the Church conferred on Hildegard. This attempt, too, was not successful; the statement from Rome made it clear that Hildegard had to be canonized first. But with or without official approval: Hildegard of Bingen has long since been viewed as a Doctor of the Church. Countless people venerate her as a saint and go on pilgrimage in her footsteps. Hildegard’s standing in her own time seems to have been as relevant as it is today. It invites a very personal response – 900 years ago as in our own day – a response that could release unknown creative powers.